Eco-501: Veracruz moist forests

Source: Wikipedia

| Veracruz moist forests | |

|---|---|

| |

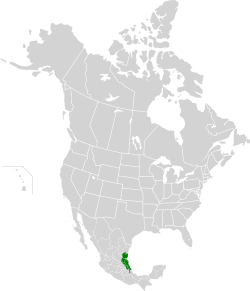

Location of the Veracruz moist forests | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Neotropical |

| Biome | Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 68,884 km2 (26,596 sq mi) |

| Country | Mexico |

| States | |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Critical/endangered |

| Protected | 2,603 km2 (4%)[1] |

The Veracruz moist forests (Spanish: Bosques húmedos de Veracruz) is a tropical moist broadleaf forests ecoregion in eastern Mexico.

Geography

The Veracruz moist forests cover an area of 69,101 km2 (26,680 sq mi), occupying a portion of Mexico's Gulf Coastal Plain between the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Gulf of Mexico. The forests extend from southern Tamaulipas across northern Veracruz, eastern San Luis Potosí, and portions of eastern Hidalgo, northeastern Puebla and northern Queretaro. The Huasteca region includes much of the ecoregion.

To the north, the forests transition to the dry lowland Tamaulipan mezquital and the upland Tamaulipan matorral. To the west, the Sierra Madre Oriental pine–oak forests occupy the higher elevations of the Sierra Madre Oriental.

The Moctezuma River and its tributaries have carved deep canyons through the Sierra Madre, which allow moist air from the Gulf of Mexico to flow further west into the plateaus and mountains, including the Sierra Gorda, and the moist forests extend westwards along the river valleys.

South of the gap where the Moctezuma River cuts through the Sierra Madre, the Veracruz montane forests and Oaxacan montane forests occupy middle slopes of the Sierra. The Veracruz dry forests separate the Veracruz moist forests from the Petén–Veracruz moist forests further south.

The northernmost extension of the Veracruz moist forests occurs in the El Cielo Biosphere and the Sierra de Tamaulipas at a latitude of about 23° 20′ degrees north.[2]

Climate

The climate of the region is tropical and humid, with rains during seven months of the year and mild variation in temperature. Average annual rainfall is 1,100–1,600 mm (43–63 in).[2]

Gallery

Flora

The canopy of this ecoregion is characterized by trees reaching a height of up to 30 m (98 ft), such as Mayan breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum), sapodilla (Manilkara zapota), rosadillo (Celtis monoica), Bursera simaruba, Dendropanax arboreus, and Sideroxylon capiri. The southern parts of the ecoregion feature mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), Manilkara zapota, Bernoullia flammea, and Astronium graveolens.[2]

Fauna

Mammals: Three species of rodents are endemic to this area, the El Carrizo deer mouse (Peromyscus ochraventer) the Tamaulipan woodrat (Neotoma angustapalata), and the Jico crested tail mouse (Habromys simulatus). Spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi), the northernmost representative of the New World primates range into this region, although it is an endangered species and not common. Marsupials include the common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis) and Mexican mouse opossum (Marmosa mexicana). Other mammals such as the Mexican anteater (Tamandua mexicana), lowland paca (Cuniculus paca), and red brocket (Mazama americana) are known from this region. Among the carnivores are the kinkajou (Potos flavus), mustelids such as tayra (Eira barbara) and greater grison (Galictis vittata), and five cat species including jaguarondi (Herpailurus yaguarondi), ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii), Puma (Puma concolor) and jaguar (Panthera onca). Just a few of the many species of bats include the elegant myotis (Myotis elegans), wrinkle-faced bat (Centurio senex), and hairy-legged vampire bat (Diphylla ecaudata).[2][3]

Birds: Endemic birds include the red-crowned amazon (Amazona viridigenalis), Altamira yellowthroat (Geothlypis flavovelata), and crimson-collared grosbeak (Rhodothraupis celaeno).[2] A few other species occurring in this region of rich avifauna include the thicket tinamou (Crypturellus cinnamomeus), bare-throated tiger heron (Tigrisoma mexicanum), boat-billed heron (Cochlearius cochlearius), plumbeous kite (Ictinia plumbea), collared forest falcon (Micrastur semitorquatus), bat falcon (Falco rufigularis), great curassow (Crax rubra), green parakeet (Psittacara holochlorus), Aztec parakeet (Eupsittula astec), yellow-headed amazon (Amazona oratrix), squirrel cuckoo (Piaya cayana), mottled owl (Strix virgata), northern potoo (Nyctibius jamaicensis), Lesson's motmot (Momotus lessonii), Amazon kingfisher (Chloroceryle amazona), lineated woodpecker (Dryocopus lineatus), pale-billed woodpecker (Campephilus guatemalensis), ivory-billed woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus flavigaster), boat-billed flycatcher (Megarynchus pitangua), Tamaulipas crow (Corvus imparatus), scrub euphonia (Euphonia affinis), and yellow-throated euphonia (Euphonia hirundinacea).[4]

Reptiles: The Morelet's crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) can be found in the remote areas of the rivers and lagoons in this region with turtles like the Mesoamerican slider (Trachemys venusta) and scorpion mud turtles (Kinosternon scorpioides). Herrera's mud turtle (Kinosternon herrerai) and the Mexican box turtle (Terrapene mexicana) are endemic to this region. Endemic lizards include the rare plain-necked glass lizard (Ophisaurus incomptus) and the Cave Tropical Night Lizard (Lepidophyma micropholis) known only from caves and the vicinity of cave openings in the Sierra Cucharas/Sierra del Abra of southern Tamaulipas adjacent San Luis Potosí. Other lizards found in the region include the silky anole (Anolis sericeus), rainbow ameiva (Holcosus undulatus), rose-belly lizard (Sceloporus variabilis), Mexican spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura acanthura), and casque-headed lizard (Laemanctus serratus). Snakes such as Iverson's threadsnake (Rena iversoni), the brown hook-nose snake (Ficimia olivacea), Taylor's cantil (Agkistrodon taylori), and the Totonacan rattlesnake (Crotalus totonacus) are largely associated with the Veracruz moist forest but all range into areas beyond the strict limits of this region. Many tropical snakes from Central America range into this region like the Central American boa constrictor (Boa imperator), Central American indigo snake (Drymarchon melanurus), blunthead tree snake (Imantodes cenchoa), Mexican parrot snake (Leptophis mexicanus), brown vine snake (Oxybelis aeneus), tropical ratsnake (Pseudelaphe flavirufa), tropical tree snake (Spilotes pullatus), green ratsnake (Senticolis triaspis), banded snail sucker (Tropidodipsas fasciata), and terrestrial snail sucker (Tropidodipsas sartorii). In addition to the cantil and Totonacan rattlesnake, venomous snakes from this province include the Texas coral snake (Micrurus tener) and the terciopelo (Bothrops asper).[5]

Amphibians: Although salamander diversity in Mexico is among the highest in the world, they mostly occur in mountainous areas.[6] The broadfoot mushroomtongue salamander (Bolitoglossa platydactyla), a lungless salamander of the Plethodontidae family, occupies the coastal lowlands from sea level up to about 1000 meters from southern Tamaulipas to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[7] The distribution of the southern subspecies of the black-spotted newt (Notophthalmus meridionalis kallerti) nearly matches that of the Veracruz moist forests region. There are also enigmatic reports of an isolated population of the lesser siren (Siren intermedia) from central Veracruz.[8] Anuran, or frog diversity in the region is higher and among the species found in this area are the Gulf Coast toad (Incilius nebulifer), cane toad (Rhinella horribilis), white-lipped frog (Leptodactylus fragilis), sabinal frog (Leptodactylus melanonotus), elegant narrow-mouthed toad (Gastrophryne elegans), sheep frog (Hypopachus variolosus), and the burrowing toad (Rhinophrynus dorsalis).[5] Godman's treefrog (Tlalocohyla godmani), can be found in the broad-leafed evergreen forest on the coastal lowlands with the painted treefrog (Tlalocohyla picta), Stauffer's treefrog (Scinax staufferi), and Mexican treefrog (Smilisca baudinii).[7][9] The veined treefrog (Trachycephalus typhonius) is a large species that produces sticky, mucous, skin secretions, presumed to deter desiccation in the dry season, as well as being a toxin to predators.[7]

Fishes: The Rio Tamesí/Pánuco system contains at least 85 species of freshwater fishes (although some of these occur in interior headwaters west of this region), where temperate and tropical taxa mingle and endemism is high.[10] One source list 93 species in the Guayalejo-Temesí watershed of Tamaulipas alone, but this includes brackish-marine species.[11] Many of the streams and rivers of this region are spring fed by karstic aquifers, providing consistent and relatively thermally stable water compared to other basins sourced largely by precipitation.[10] The karstic environment of the Sierra Madre Oriental produces many caves and subterranean waterways that ultimately surface near the base of the mountains in the west of this region. Some fish like the endemic phantom blindcat (Prietella lundbergi) are adapted to caves and have been collected at depths of 50 meters in cave systems of the Rio Frio (in the Rio Guayalejo drainage). Some populations of the Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus [= A. jordani]) also inhabit caves and are blind, although other populations of the same species living in surface streams have eyes, while still other populations are intermediate.[10][11] The region is rich in platyfish and swordtail (Xiphophorus) diversity including sheepshead swordtail (Xiphophorus birchmanni), delicate swordtail (Xiphophorus cortezi), mountain swordtail (Xiphophorus nezahualcoyotl), and the endemic variable platyfish (Xiphophorus variatus). Cichlid diversity is also high in this area including the lowland cichlid (Herichthys carpintis) and endemic species like the chairel cichlid (Herichthys [Nosferatu] pantostictus) and Nautla cichlid (Herichthys deppii) among others. Other fishes include the pigmy shiner (Notropis tropicus), Forlón gambusia (Gambusia regani), gulf gambusia (Gambusia vittata), chubsucker minnow (Dionda erimyzonops), and the endemic lantern minnow (Dionda ipni).[10][11] Conservation threats of fishes include, damming of waterways, water diversion for agriculture, runoff associated with agriculture and livestock, oil and industrial contamination, invasive species, and irresponsible recreational activities.[11]

Conservation and threats

The forests have been heavily altered by human activity, so that only a few enclaves of mature forest remain. Forests have been cleared for timber harvesting, agriculture, and grazing, and much of the original forest has been replaced with scrubland or secondary forest.

Protected areas

7.66% of the ecoregion is in protected areas. Protected areas entirely or partly within the ecoregion include El Cielo, Sierra del Abra Tanchipa, Sierra Gorda, Sierra Gorda de Guanajuato, and Sierra de Tamaulipas biosphere reserves, Laguna Madre and Río Bravo Delta Flora and Fauna Protection Area, Bernal de Horcasitas, El Sótano de Las Golondrinas, and La Hoya de las Huahuas natural monuments, Río Filo-Bobos y su Entorno protected area, and Zona Protectora Forestal Vedada Cuenca Hidrográfica del Río Necaxa natural resources protection area.[12]

See also

External links

- "Veracruz moist forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Veracruz moist forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08.

References

- ↑ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; et al. (June 2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) Supplemental material 2 table S1b. - 1 2 3 4 5 "Veracruz moist forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund., accessed 18 Dec 2014

- ↑ Ceballos, G. Ed. (2014). Mammals of Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. xiii, 957 pp. ISBN 1-4214-0843-0

- ↑ Howell, S. N. G. and S. Webb. (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Cantral America. Oxford University Press. Oxford. xvi, 851 pp. ISBN 0-19-854012-4

- 1 2 Lemos Espinal, J. A., Editor. (2015). Amphibians and Reptiles of the US-Border States. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, Texas. x, 614 pp. ISBN 978-1-62349-306-6

- ↑ Duellman, William E. 1999. Patterns of Distribution of Amphibians: A Global Perspective. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. viii, 633 pp. ISBN 0-8018-6115-2

- 1 2 3 Lemos Espinal, Julio A. and James R. Dixon. 2013. Amphibians and Reptiles of San Luis Potosi. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Inc. Eagle Mountain, Utah. xii, 300 pp. ISBN 978-0-9720154-7-9

- ↑ Ramirez-Bautista, A., O. Flores-Villela, and G. Casas-Andreu. 1982. New herpetological state records for Mexico. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society, 18(3): 167-169.

- ↑ Duellman, W. E. 2001. The Hylid Frogs of Middle America, Vol. I & II. Contributions to Herpetology. Vol. 18. Society for the Study Amphibians and Reptiles. xvi, 1159 pp. ISBN 0-916984-56-7

- 1 2 3 4 Miller, R. R., W. L. Minckley, and S. M. Norris. (2005). Freshwater Fishes of Mexico. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. xxv, 490 pp. ISBN 0-226-52604-6

- 1 2 3 4 García de León, Francisco J., Delladira Gutiérrez Tirado, Dean A. Hendrickson, and Héctor Espinosa Pérez (2005). Fishes of the Continental Waters of Tamaulipas: Diversity and Conservation Status. In Jean-Luc E. Cartron, Gerardo Ceballos, and Richard S. Felger (eds.). Biodiversity, Ecosystems, and Conservation in Northern Mexico. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, N. Y. xvi, 496 pp. ISBN 0-19-515672-2

- ↑ "Veracruz moist forests". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 4 October 2021.